Blood vs Noise

The DNA Lie That Sounds Like Family

I almost assigned Earl the wrong parents.

Not because the records were thin.

Because the DNA was convincing.

It arrived with confidence.

It arrived with names.

It arrived with just enough overlap to feel like relief.

After years of silence on paper, autosomal DNA showed up like a witness who wanted to talk.

And for a moment, I believed it.

That moment almost ended the case.

DNA doesn’t lie loudly. It lies convincingly

Here’s what I’ve learned over the years. I’m not looking for comfort in the match list. I’m not looking for familiar surnames or trees that make me feel like I’m getting warmer. I’m looking for DNA that can survive interrogation and scrutiny. Centimorgans are the first lie detector. Anything under about 10 cM walks into the room already on probation. It can talk, but it can’t testify. Clusters of tiny segments don’t impress me. They chatter. They echo. They create the illusion of momentum while saying nothing concrete. One clean segment in the 25 to 50 cM range carries more authority than a dozen polite maybes stacked on top of each other. I want segments that show up intact, in the same location, refusing to break apart when pressure is applied. If a match can’t stand on its own centimorgans without emotional assistance, it doesn’t belong anywhere near Earl’s parents.

Eventually, I’ll present the tool that actually puts small centimorgan matches to work. If you think you know what it is I’m talking about; put it in the comments below. For now, allow me to linger in prose. I digress.

Access to Colleen’s autosomal DNA matches changes the geometry of the room. She’s not another dot on the chart. She’s a biological witness, one generation closer to the crime scene. Her DNA carries longer segments, less eroded by time, louder and harder to fake. When a match shows up at 30, 40, or 60 cM through her, it stops being a suggestion and starts being evidence. When that same segment appears in my results at the same chromosomal address, the noise clears its throat and leaves. Small segments that once felt persuasive evaporate under her signal. Triangulation stops being theoretical and starts behaving like a chokehold. With Colleen in the case, centimorgans stop lying politely and start telling the truth whether they want to or not. The match list no longer feels like a crowd. It feels like a lineup.

At least, it should feel that way.

Because once I start working through Colleen’s matches, the case doesn’t simplify. It deepens. The rabbit hole widens. Every answer creates two more questions. This isn’t an easy ride.

The Case Question

Here’s the question that matters.

Did Earl’s DNA point to his parents

or did it point to population noise wearing a familiar surname?

Because those two things look identical on a screen.

The stake was permanent.

Once a parent gets attached to Earl, that decision doesn’t stay private.

It propagates.

It becomes reference.

It turns into truth for someone else.

So I slowed down.

What Earl’s DNA Actually Gave Me

Autosomal DNA didn’t give me parents.

It gave me shared, short autosomal DNA segments.

That distinction matters more in Earl’s case than anywhere else.

Because Earl’s paper trail begins with a vacuum.

No parents listed.

No recorded mother.

No father acknowledged.

No early childhood stability.

DNA felt like the first honest thing in the file.

That’s exactly why it needed to be interrogated.

The First Lie That Sounded Like Family

The early matches looked promising.

Shared surnames.

Shared regions.

Clusters that repeated just enough to feel directional.

It looked like lineage trying to surface.

But what I was seeing wasn’t inheritance.

It was overlap.

Earl’s DNA didn’t lie loudly.

It lied convincingly.

Blood Versus Noise in Earl’s Genome

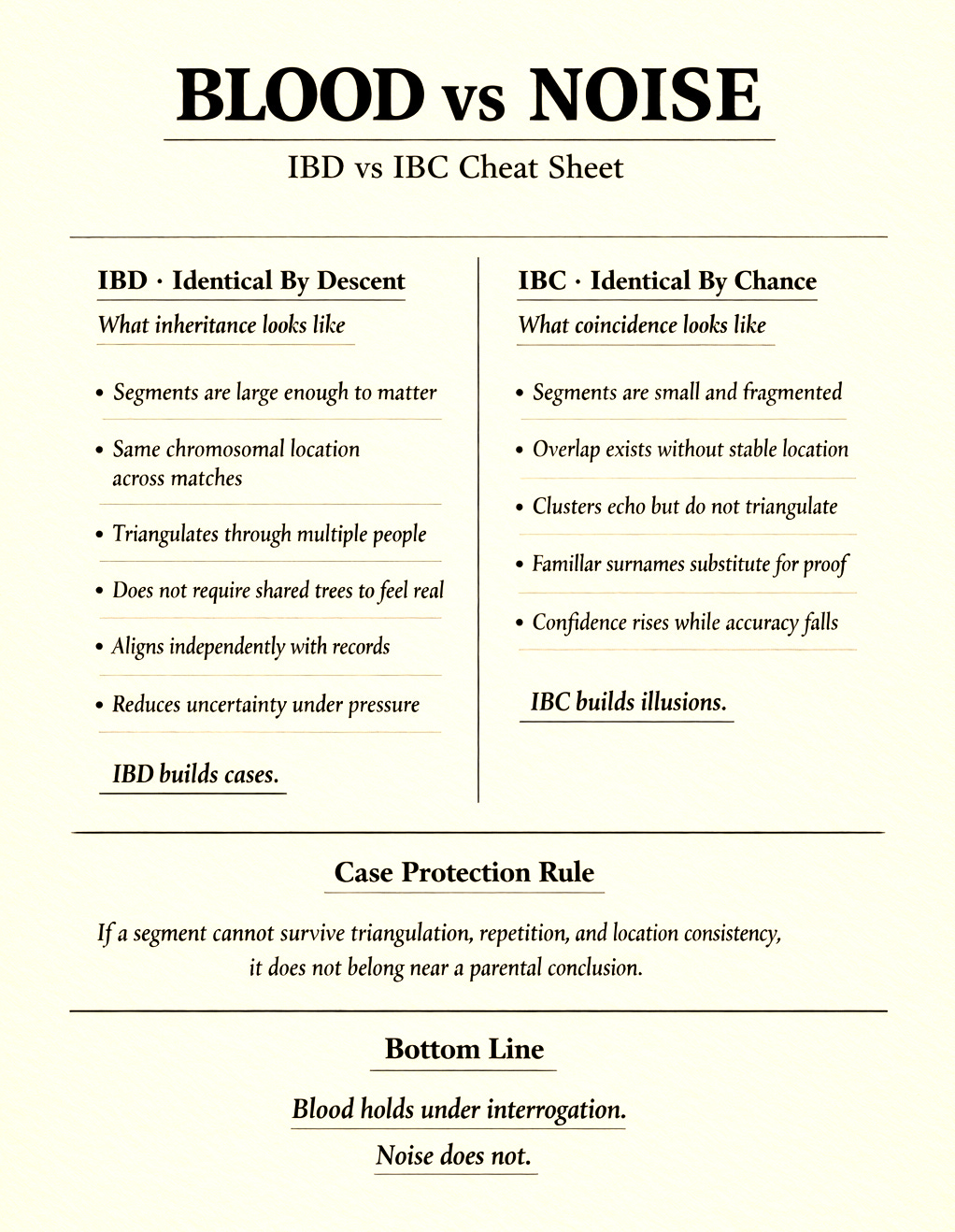

Before I could even think about names or parents, I had to confront a harder problem. What kind of signal was I actually looking at. Earl’s DNA didn’t arrive with a clear voice. It arrived fragmented, overlapping, and persuasive in the way only partial evidence can be. Every match carried the same implication. We share something. But sharing isn’t lineage. Shared DNA can point to inheritance, or it can point to population memory. Those two outcomes produce identical screens and radically different truths. If I misread that distinction at the start, every conclusion that followed would be contaminated. This wasn’t a matter of terminology or technique. It was a matter of whether Earl’s genome was pointing backward to a real biological line, or sideways into statistical coincidence. Until that question was answered, nothing else in the case was safe.

In Earl’s case, the difference between Identical By Descent and Identical By Chance wasn’t academic.

It was structural.

Identical By Descent would mean a real ancestral line.

Identical By Chance would mean coincidence dressed up as proximity.

Small segments dominated the early match list.

They clustered.

They echoed.

They tempted attachment.

That’s where IBC lives.

And it nearly rewrote Earl’s origin story.

Why Small Segments Nearly Closed the Case

The small matches felt productive.

There were many of them.

They agreed with each other.

They pointed toward familiar geographic lanes.

But none of them triangulated cleanly.

No shared segment held under pressure.

The DNA looked like it wanted to talk.

It just couldn’t say the same thing twice.

That’s not blood behavior.

That’s noise.

The Algorithm Does Not Care About Earl

The platform surfaces hints.

Trees align just enough to feel helpful.

Confidence bars glow politely.

But the algorithm doesn’t know Earl.

It doesn’t know the silence in his birth record.

It doesn’t know the stakes of attaching the wrong parents to a man whose entire life was shaped by absence.

The software is doing its job.

I have to do mine.

When Noise Masquerades as Maternal Lines

Here’s where Earl’s case gets dangerous.

Certain clusters suggest maternal continuity.

The names repeat.

The regions overlap.

It looks like a mother trying to appear through DNA.

But the segments don’t triangulate.

They drift.

They overlap without anchoring.

This isn’t descent.

This is population memory.

The Test That Saves the Case

I force triangulation.

Segments that can’t hold position are stripped of authority.

Clusters without shared ancestry are downgraded to noise.

Trees that relied on repetition instead of inheritance are dismissed.

What survives is quieter.

But it’s real.

Blood survives interrogation. Noise does not.

Initial Analysis

Here’s the part I didn’t expect.

The more noise I remove, the lonelier the case becomes.

Fewer matches.

Less apparent direction.

Less comfort.

And that loneliness feels familiar.

It matches Earl’s early life better than the abundance ever did.

That was the moment I realized something uncomfortable.

DNA had tried to give Earl parents he never had.

What Earl’s DNA Is Really Showing Me

Earl’s genome carries population signal.

It carries ancient overlap.

It carries statistical coincidence.

What it doesn’t carry easily is a clean parental handoff.

That absence matters.

It suggests instability.

It suggests fragmentation.

It suggests that Earl’s beginnings weren’t anchored in the way genealogists want them to be.

DNA doesn’t contradict the record.

It mirrors it.

The Cheat Sheet That Protects Earl

This becomes non-negotiable.

Identical By Descent can move the case forward.

Identical By Chance can only distract it.

Every segment has to earn its authority.

Every match has to survive triangulation.

Every conclusion has to stand without emotional assistance.

Earl doesn’t need a tidy story.

He needs a true one.

Open Loop Reopened

So here’s the unanswered question again.

If DNA didn’t give Earl his parents, what did it give him?

The answer is coming.

But not yet.

Conclusion

Autosomal DNA doesn’t solve Earl’s case.

It tries to rush it.

It tries to replace silence with certainty.

But Earl’s story is never going to be loud.

The truth about his origins isn’t hidden in abundance.

It’s hidden in restraint.

DNA doesn’t betray Earl.

It reveals the shape of his absence.

And once you see that,

you stop asking DNA to comfort you

and start asking it to tell the truth.

A Word About Triangulation

Triangulation is the spine of this work, and it gets its own case file. I mention it here only long enough to mark the line between inheritance and coincidence. Anything more would be malpractice. Triangulation doesn’t survive compression, and this case doesn’t tolerate shortcuts.

Guess the Technique

At the beginning of this post, I wrote this out:

Eventually, I’ll present the tool that actually puts small centimorgan matches to work. If you think you know what it is I’m talking about; put it in the comments below. So, if you know what this technique is, or can think of the BEST way to make small segments work for you 100% of the time or at least with great accuracy. Place it below in the comments. I’ll give you one hint:

It’s a simple technique but it’s super tedious. Think outside the box!

Go!

Receipts

Bettinger, Blaine T. The Family Tree Guide to DNA Testing and Genetic Genealogy. Cincinnati: Family Tree Books, 2016.

Bettinger, Blaine T. “Identical by Descent (IBD) vs. Identical by Chance (IBC).” The Genetic Genealogist. Accessed January 2026. https://thegeneticgenealogist.com.

Bettinger, Blaine T. “The Shared cM Project.” The Genetic Genealogist. Accessed January 2026. https://thegeneticgenealogist.com.

Estes, Roberta. “Triangulation for Autosomal DNA.” DNAeXplained. Accessed January 2026. https://dna-explained.com.

International Society of Genetic Genealogy. “Autosomal DNA Statistics.” ISOGG Wiki. Accessed January 2026. https://isogg.org/wiki/Autosomal_DNA_statistics.

International Society of Genetic Genealogy. “Identical by Descent.” ISOGG Wiki. Accessed January 2026. https://isogg.org/wiki/Identical_by_descent.

International Society of Genetic Genealogy. “Triangulation.” ISOGG Wiki. Accessed January 2026. https://isogg.org/wiki/Triangulation.

International Society of Genetic Genealogy. “Recombination.” ISOGG Wiki. Accessed January 2026. https://isogg.org/wiki/Recombination.

Janzen, Timothy B. “The Danger of Small Segments.” International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki. Accessed January 2026. https://isogg.org/wiki.

Jones, Thomas W. Mastering Genealogical Proof. Arlington, VA: National Genealogical Society, 2013.

Kennett, Debbie. DNA and Social Networking: A Guide to Genealogy in the Twenty-First Century. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2011.

Mills, Elizabeth Shown. Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2015.

Erlich, Yaniv, Tal Shor, Itsik Pe’er, and Shai Carmi. “Identity Inference of Genomic Data Using Long-Range Familial Searches.” Science 362, no. 6415 (2018): 690–694.

Excellent post as ever Nate and the truth is the DNA definitely didn't lie! Earl's DNA tells an almost identical story to his documented trail, almost non-existent! The DNA in fact confirms what you already know, very little. But and here's the but, the DNA could potentially solve the puzzle in the future should a closer DNA match materialise..........the DNA is out there, you're just fishing in a big pond looking for that one big bite my friend!

As you rightly point out, it is important to be weary of low value matches. The lower they are the higher the probability of being IBC. In addition, even if the lower ones are IBD, they may be segments that have passed down unbroken for generations and generations and point to an ancestor who is untraceable (such is the randomness of DNA inheritance).

I am always wary of the incompleteness of my tree since knowing that a group of matches triangulate to a common ancestor is one thing, knowing who that ancestor is is quite another ... Even when all the matches are genealogically connected to a particular ancestor. What if all those matches who connect via Ancestor A, also happen to share a connection via another as yet unknown/undiscovered ancestor. How many of us have such complete trees that we can be absolutely sure we don't connect to matches in more ways than one. You can't be sure you have triangulated to the right ancestor (the one the segment came from) unless you are sure you couldn't have inherited the segment through a different line.

You mentioned tools - DNA Painter is my main "go to" - https://dnapainter.com/ For example, the Chromosome Painter to visualise how the shared match segments line up; WATO to check for the possibility/probabilities of the relationships with the matches assuming the identified ancestor is the correct one (for matches over 40cM); the shared cM project calculator to check for possibilities/ probabilities for matches less than 40cM ... There are lots of tools on DNAPainter - You can even check your tree completeness.

Here is an article you may want to read if you haven't already - Leah Larkin - https://thednageek.com/low-matches-lie/