A Child Nobody Claimed

How absence becomes evidence before DNA ever enters the room

Nobody loses a childhood by accident.

If a child grows up without parents, without permanence, without anyone willing to put their name beside his, something went wrong long before the paperwork failed. Records don’t erase people. People do.

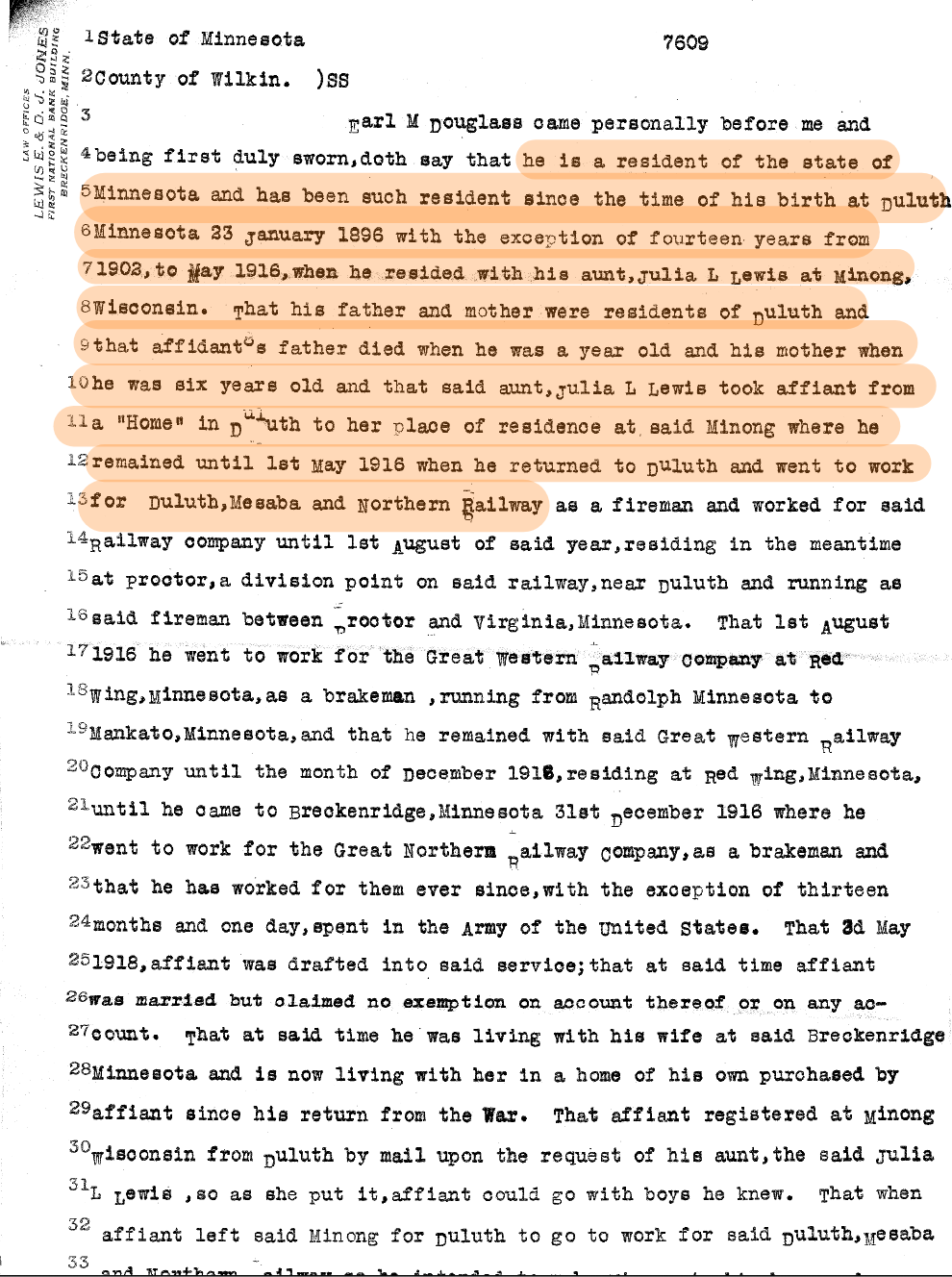

Earl Mack Douglas didn’t disappear as a child. He was left unclaimed.

Records don’t erase people. People do.

He wasn’t protected by family and he wasn’t protected by the state. Not in the way people imagine protection. In the early years there’s no stable adult advocate in the file. No durable safety net. Just a child moving through other people’s space until someone finally files him.

He wasn’t outside the record. He was outside the safety net.

There are plenty of ways to lose a child.

Sometimes it’s loud. Fire. Disease. Court orders. Headlines.

Sometimes it’s quiet. On paper. In margins. In the space where two names should be.

That’s how Earl goes missing in the early record. Not because he vanished. Because no adult ever stepped forward to say, “This one is mine.”

There isn’t one clean document that explains Earl’s childhood. There’s one exception. An affidavit buried in his World War I bonus file. The kind of thing you only find after you’ve checked everything. Twice. The kind of thing that shows up after curiosity dies and commitment takes over.

In it, Julia L. Lewis says Earl was taken from a “home” in Duluth in 1902.

That sentence isn’t a solution. It’s a trapdoor.

Because what does “home” mean in 1902 Duluth?

It could mean a family home.

It could mean a rented room.

It could mean a boarding house where nobody asked questions.

It could mean an orphanage.

It could mean a shelter.

It could mean a placement.

It could mean a bad situation someone wanted handled quietly.

It could mean something safe.

It could mean something ugly.

It could mean anything.

That’s the problem.

The word is elastic. The truth isn’t.

Home is a clean word used to cover messy realities. It smooths edges. It protects institutions. It spares adults. It doesn’t spare the child.

And “aunt” does the same work.

Julia L. Lewis calls herself his aunt, but the record treats her like what she really was. A caretaker. A guardian. An adult assigned to keep a child from becoming a public problem. “Aunt” makes it sound like family stepped up. Guardianship says the state had to get involved.

“Aunt” is the softer label that makes custody sound like love.

Caretaker is the real job.

Those words are polite and radioactive. They soften the act while exposing it.

They imply removal.

They imply authority.

They imply a decision got made over a child’s head.

They imply adults were in the room.

Just not the ones who should’ve been.

Duluth. 1902. Taken from a “home.”

Say it out loud. You can feel what it refuses to say.

Sterile words can hide violent facts.

What the modern world gets wrong about births

We expect a birth certificate like it’s gravity. Of course it exists. Of course it’s filed. Of course it has names. Of course it has witnesses.

That’s a modern fantasy.

Back then, vital records weren’t a clean national machine. They were a patchwork. Local habit. Civic improvisation. Church notes. County ledgers. Midwives delivering babies while paperwork lagged behind. A birth could be real and still never become official in the way we’d recognize today.

Before the system matured, a birth record wasn’t automatic. It was a choice someone had to make.

That matters in Duluth in 1896.

If Earl was born there, he was more likely born outside a hospital than inside one. A room. A rented space. A bed that didn’t belong to anyone who wanted attention. A midwife. Maybe a doctor if money or connections existed. That was common in the period. The missing birth certificate doesn’t prove it. It supports it.

Then public health hardened everything.

Once cities needed numbers for disease, sanitation, and infant death, births stopped being private events and started becoming infrastructure. States got pushed into standard practice. Not with one dramatic order. With standards. With pressure. With the slow humiliation of being the place that didn’t count.

That’s how compliance spreads. Through legitimacy.

Minnesota’s record system gets steadier around the turn of the century. The dependable machine people assume has always existed is mostly a twentieth century creation.

Duluth makes everything more volatile.

Port towns run on movement. Labor. Arrivals. Departures. Rented rooms. Boarding houses. Privacy as currency. In that world, paperwork isn’t neutral. Paper exposes people. It fixes a name in place. It makes a private situation public.

So yes, a missing birth record can be a clue. It can also be the era. A system still learning how to count bodies. A city built on motion. A birth that happens in a room, not a ward. A story that starts quietly because quiet is how you survive.

There’s no photograph of a mother holding him. There’s no father’s signature anchoring him to a place or a family. Instead, there are fragments. Addresses that change too often. Adults who appear briefly and then dissolve back into the record. Institutions that step in because someone has to.

This isn’t a story about missing records. It’s a story about missing adults.

This isn’t a story about missing records. It’s a story about missing adults.

The first thing that goes missing

When genealogists talk about brick walls, they usually mean documents. A census that disappears. A birth record that doesn’t list parents. A courthouse fire. A clerical error.

That framing is comforting. It keeps the problem technical. It lets everyone pretend the truth is sitting in a drawer somewhere. Waiting.

But Earl’s wall wasn’t made of paper. It was made of people who never stood still long enough to be counted.

From the beginning, Earl exists without a stable adult orbit. He isn’t raised in a household that accumulates evidence over time. There’s no long term address that keeps producing proof. There’s no consistent adult presence that stays visible. Instead, Earl moves.

Not once. Not twice. Repeatedly. Across towns. Across counties. Across jurisdictions.

That movement has a signature. It isn’t ambition. It isn’t opportunity. It’s contingency. Being placed. Being passed along. Living where space exists, not where roots grow.

Kids raised this way don’t experience instability as an event. They experience it as an environment.

Instability wasn’t a detour. It was the setting.

When a kid grows up in motion, the body learns motion. The nervous system learns scanning. The mind learns not to expect permanence. That doesn’t show up as one dramatic moment. It shows up as baseline.

Instability wasn’t a detour. It was the setting.

Two childhoods, one life

All of Earl Mack Douglas’s surviving documents suggest a life built on contradiction.

Every assessment promises clarity. It delivers more questions. Dates align. Meaning doesn’t. Addresses appear. Then vanish. Adults get named. Nobody gets explained.

After years of returning to the same records, one conclusion becomes unavoidable.

Earl Mack Douglas didn’t have one childhood. He had two.

The first exists mostly in shadow. From birth until around age six, Earl appears to have lived with his mother in Duluth. That period is defined less by what’s documented and more by what’s implied. The record suggests stability without detail. A city with work. A household that didn’t attract court attention. A child who, for a short window, seems to have existed inside something close to ordinary life.

Then that childhood ends.

Around 1902, Earl’s life fractures. The mother disappears from the record. The city disappears. The assumption of parental care disappears with it. What follows isn’t gradual. It’s a clean break.

And the only clean sentence that bridges the break is the affidavit.

Taken from a “home” in Duluth, 1902.

The second childhood begins in Minong under the guardianship of Julia L. Lewis. That period is better documented. It’s also colder. It carries institutional fingerprints, not family warmth. Oversight replaces intimacy. Permanence gets replaced by management.

These two childhoods don’t overlap. They don’t explain each other. They sit side by side like mismatched halves of the same life.

The first childhood suggests attachment.

The second suggests adaptation.

That division matters.

Kids don’t reset when circumstances change. They carry the first environment into the second. They adapt. They don’t forget. When a child goes from private care to administrative management, the loss isn’t only personal. It’s developmental.

He didn’t have one childhood. He had two.

Childhood without buffering

In families with protection, childhood is buffered. When a parent fails, another adult steps in. When money runs short, someone covers it. When illness hits, the household absorbs the shock.

Earl didn’t have that buffer.

There’s no evidence of a permanent caregiver invested in his long term well being. Guardians appear, but guardianship isn’t parenthood. It’s administrative care. It keeps a kid alive. It doesn’t necessarily keep a kid anchored.

A guardian’s obligation is legal. A parent’s obligation is existential.

That distinction matters.

Kids raised without buffering learn early that the world won’t reorganize itself around them. They adapt downward. They become portable. They learn not to accumulate attachments that can be taken away.

None of this gets stamped in a census. But it shows up later. In movement patterns. In work choices. In what a person can tolerate without protest.

That’s how childhood leaves fingerprints without leaving a diary.

And the fingerprints aren’t just social.

A childhood like this trains a nervous system. It teaches the body what to expect. It teaches a kid what danger feels like. It teaches them what normal feels like. Those lessons don’t stay in the mind. They settle lower. They get carried forward as reflex and tolerance and baseline.

A childhood like this trains a nervous system.

The geography of being unclaimed

Earl’s early years are defined by geography, but not in the romantic way genealogy loves to sell. These aren’t migrations driven by dreams or destiny. These are short distance relocations that suggest placement, not choice.

Each move answers one practical question.

Where can this child go now.

That question doesn’t exist when a child has parents who can say no.

Movement like this teaches a brutal lesson. Permanence isn’t guaranteed. Belonging is conditional. Stability is borrowed.

And borrowed stability teaches you not to rely on it.

That matters later. It matters in relationships. It matters in risk tolerance. It matters in how much silence someone can live with before they call it normal.

A childhood built on contingency produces adults who treat uncertainty as familiar terrain.

Institutions step in when people step out

When parents disappear from the record, institutions fill the vacuum. Not out of compassion. Out of necessity.

Courts appoint guardians. Counties track dependents. Schools record attendance. Employers record labor. The state becomes the longest lasting adult in the room.

But institutions don’t raise children. They manage them.

They don’t ask what a child needs to become whole. They ask what a child needs to stop becoming a problem.

By the time the state shows up, the damage is already old.

The record tells us Earl survived. It doesn’t tell us he was protected.

Those are different outcomes.

The limits of trying harder

My research into Earl Mack Douglas’s early life has been exhaustive.

There isn’t much anyone can suggest that I haven’t already tried, revisited, or chased into the ground. I’ve searched the obvious archives and the obscure ones. I’ve followed leads that dissolved. Then I returned years later to confirm they were still empty. I’ve paid genealogists and professional researchers. I’ve compared conclusions. I’ve reviewed methods as carefully as my own.

What I learned from other genealogists wasn’t new information about Earl.

I learned the scope of their research.

I learned the limits of their imagination.

I learned how often the urge to be helpful gets bent by ego.

This isn’t a tantrum. It’s a pattern.

Most researchers are trained to look for what exists. They’re less comfortable sitting with what doesn’t. When records thin out, the instinct is to assume the search failed. Not that the absence might be the result.

Trying harder doesn’t create records that were never generated. Paying for expertise doesn’t summon adults who chose not to be visible. At a certain point, diligence stops being the problem.

The problem is structural. It’s engineered unknown.

Trying harder doesn’t create records that were never generated.

The moment it stopped being Research

Here’s the part I didn’t expect.

The longer I chased paper, the more I realized I wasn’t only hunting names. I was trying to do something no one did for him when it mattered.

I was trying to claim him.

Not legally. Not biologically. Not in a way that fixes what happened. In the simplest human way. The way a child should’ve been claimed in the first place. With attention. With persistence. With refusal. Refusal to let him stay unnamed in the place where adults belong.

That’s why this work doesn’t feel like a hobby. A hobby can be put down. This can’t. Not when the origin story is a void and the void has consequences.

It’s easy to treat missing parents like a puzzle. It’s harder to admit what it really is.

It’s a childhood without witnesses.

I was trying to claim him.

Why the paper trail feels thin

People assume the record is incomplete because of chance. Bad luck. Clerical failure.

That assumption is wrong.

The paper trail is thin because Earl’s childhood didn’t generate the stable social life that produces documentation. Records follow stability. They accumulate around families who stay put. Who live at one address long enough to become visible.

Earl didn’t have that kind of childhood.

That’s why searching harder doesn’t solve it. You can exhaust every archive and still miss what was never created.

The absence is the evidence.

The real crime scene

This story isn’t about missing records. It’s about missing adults.

It’s about a child who lived long enough to become a man, but never had the basic protection that turns childhood into a foundation instead of a storm.

If you want the truth of Earl Mack Douglas, don’t start with a document. Start with the question that makes documents possible.

Who was supposed to stand there, and didn’t.

Because that’s the real crime scene.

Not the courthouse. Not the census. Not the file.

The empty space where a parent should be.

So that’s where I’m staying. Right at the gap. Until it gives up a name.

Who was supposed to stand there, and didn’t.

Receipts

State of Minnesota, Soldier’s Bonus Board, WWI Bonus File and Documents for Earl Mack Douglas, Warrant File no. 73717 (St. Paul, MN, 1919), affidavit of Julia L. Lewis, [date if shown], [page or image number].

Minnesota Historical Society, “Minnesota Birth Records, Help/About,” accessed December 14, 2025.

Minnesota Department of Health, “Minnesota Vital Records and Certificates,” accessed December 14, 2025. Minnesota Department of Health

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, “Home Births in the United States, 1990–2009,” NCHS Data Brief no. 84 (March 2012). CDC

Duluth Seaway Port Authority, “Port Operations,” accessed December 14, 2025. Port Authority

National Research Council, Vital Statistics: Summary of a Workshop (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2013), “Context and Background.” NCBI

Such a powerful read Nate!! About halfway through I already knew that you was trying to claim him and bring him home to give him a sense of belonging that had been missing from his early years.

Looking forward to what you found via DNA.